Have you ever wanted to escape civilization to some remote sunny island? I know I do (sometimes). And that’s why I relate some ways to Paul Gauguin, despite his lifestyle. He rejected the modernity and noise of bourgeois France, preferring the (then) far-flung islands of French Polynesia.

Granted, Paul Gauguin is a divisive figure in the art world.

On one end, he was a self-taught, artistic genius whose bold, expressive style paved the way for the resurgence of Primitivism in art. And on the other, he was a guy who left his family behind to become an artist in an exoticized island paradise. Not to mention, when Gauguin arrived at the said exotic island of Tahiti, he got married a second time to a 15-year-old girl named Teha’amana.

Art historians now have the responsibility to contextualize Paul Gauguin, his life, and his westernized view of the primitive—particularly, his treatment of Tahitian women in both art and attitude.

Love him or hate him, you can’t discount his contributions to the timeline of art history. Gauguin’s devotion to his art and his pursuit of life’s greatest truths cemented his place as one of the most influential French artists of all time.

Who was Paul Gauguin and what is he known for?

"Art is either plagiarism or revolution." - Paul Gauguin

Full Name: Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin

Date of Birth: 7 June 1848

Place of Birth: Paris, France

Date of Death: 8 May 1903

Place of Death: Atuona, Hiva Oa, Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia

Known for: Paul Gauguin was a key figure in the Symbolist movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He’s best known for developing Synthetism, a post-Impressionist art style, and for painting from feeling and imagination rather than classical perspective. Gauguin’s work later influenced many modern artists like Pablo Picasso.

12 facts about Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin was a French painter, sculptor, and print-maker. An important figure who catalyzed many developments in 19th and 20th-century art, though he never quite got the recognition while he was alive. He began his artistic career with the Impressionists before breaking away from the movement to develop his own artistic style.

A key figure in the post-Impressionist movement, Gauguin experimented with expressive forms, colors, and compositions. He called this style “Synthetism,” which is characterized by large plains of color and vibrant outlines.

His later artworks are mystical and symbolic. Primitive yet emotional. Much influenced by the French Polynesian isles where he self-exiled and eventually died. His eccentric lifestyle and carefully curated public personality make him a memorable—perhaps problematic?—figure in art history.

With that, let’s take a look at Paul Gauguin’s controversial life, one fast fact at a time.

Aline Maria Chazal, Paul Gauguin’s mother, is descended from Peruvian nobility

Paul Gauguin was born in Paris to journalist Clovis Gauguin and French-Peruvian Aline Chazal.

Gauguin’s mother, Aline was the daughter of feminist-activist Flora Tristan, of the Spanish-Peruvian Moscoso family. Don Mariano Tristán y Moscoso, Gauguin’s great-grandfather, belonged to an old and aristocratic Spanish-Peruvian family established in Arequipa, Peru. Despite her noble family ties, however, Aline Chazal and her mother were cut off from the family fortune.

Gauguin’s family history is quite a colorful one. His maternal grandmother made great contributions to feminist history. She also survived a violent marriage—one that ended with attempted murder.

In 1850, Clovis Gauguin moved his family to Peru—both to escape Napoleon III’s France and establish a Republican magazine in Lima. Unfortunately, he died on the journey. Arriving in Peru a widow and single mother of two, Aline Chazal was welcomed by her extended family.

Gauguin’s obsession with primitivism and faraway exotic places began in his childhood

Gauguin identified as a “savage” soul—to him that meant being primitive, wild, and free. He even claimed to be of Incan descent, but that was far from the truth. He spent his early childhood in the upper echelons of South America.

The Gauguin family lived in Lima for the next four years. They stayed in the presidential palace. Gauguin’s mother was distantly related to José Rufino Echenique, the president of Peru at the time.

They returned to Paris when Paul Gauguin was 7 years old. But that brief period made a great impact on Gauguin’s perspective. In his memoirs, Gauguin would repaint Peru as an exotic, colorful, and primitive world. One that he would relentlessly search for all his life.

He became an artist when he was almost 40 years old

It’s never too late to pursue your passions. It’s better to find them later than never at all. Gauguin’s life is proof of that. He didn’t become a full-time artist until the age of 35.

At 17, Paul Gauguin became a sailing merchant. This could also have contributed to his endless wanderlust. He spent a few years at sea until his mother passed away in 1867. A family friend, Gustave Arosa, assumed custody of the Gauguins. Arosa helped Paul get a job as a stockbroker and eventually introduced him to his wife Mette Sophie Gad.

As a stockbroker, Paul Gauguin was earning good money. He started painting as a personal hobby. When he wasn’t working, he’d visit galleries and hang out with the artists who frequented a cafe near his home. These artists turned out to be the Impressionists. Gauguin would form a friendship with Camille Pissarro and Paul Cézanne.

His career as a banker came to an abrupt end when the French stock market crashed in 1882.

He was largely a self-taught artist

Paul Gauguin would paint on Sundays in Camille Pissarro’s home in France. Pissarro would teach Gauguin all about painting in the Impressionist style. After losing his stockbroker job in the 1882 French stock market crash, he began spending every day painting. In a way, painting became Gauguin’s source of happiness, an outlet to cope with the stress and loss of his job.

But he never had a formal education in the arts.

Gauguin found much inspiration from the Impressionists as well as Japanese wood prints and stained-glass windows. During his time as a stockbroker, he’d amassed a sizeable art collection.

Though Gauguin enjoyed painting, it wasn’t very lucrative. Gauguin exhibited with the Impressionists at the beginning of his artistic career but received little attention compared to his contemporaries.

In the end, his budding painting career caused some strain on his family life. He left his wife Mette and their kids in Copenhagen to pursue art full-time.

After moving away from Paris (and the Impressionists) Gauguin developed his signature style called Synthetism

Devoted to painting every day for the rest of his life, the artist set forth on his travels.

He began a modest, nomadic artist’s life, traveling from Paris to Brittany to Martinique in the French Caribbean to Tahiti to the Marquesas Islands. The further Gauguin got from civilization and closer to his ideal “primitive” life, the more mature and symbolic his artworks became.

These travels inspired his new style which he called Synthetism. Simply put, it’s an art style that synthesizes the subjects in a painting with the painter’s perspective. This style is defined by large areas of color and shapes that are defined by dark outlines.

This art style reflects Gauguin’s poetics: that art must synthesize the subject’s form with the artist’s feelings, imaginations, and aesthetics.

Eventually, Synthetism would inspire later modern art styles like Fauvism, Symbolism, and Cubism.

Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin were close friends, until the incident with the ear

As per Theo Van Gogh’s suggestion, Paul Gauguin went to live with Vincent Van Gogh in his now-famous Yellow House in Arles. On the 23rd of October in 1888, Gauguin finally moved in. The two artists painted together, experimenting with expressive uses of color and painting by imagination rather than by sight. The rest of the time, they likely argued over the meaning of art.

Their friendship ended with the infamous incident regarding Vincent Van Gogh’s ear.

There are two versions of the story. One where Van Gogh threatens Gauguin with a razor and then cuts off his own ear. Another where Gauguin, instead of Van Gogh, was responsible. People say that Gauguin, a decent swordsman, used a sword and not a razor.

Spoiler alert, the second version has been debunked. But it’s an interesting twist to the story.

What really happened?

Van Gogh is known to have a volatile personality, prone to frequent outbursts. Suffice to say, the friendship deteriorated to the point where Gauguin decided to leave Arles.

One evening, Van Gogh confronts Gauguin with a blade. Paul Gauguin leaves Vincent Van Gogh alone in the Yellow House. That same evening, Van Gogh cuts off a part of his ear, wraps it in a paper, and leaves it with a woman at a brothel Gauguin frequented.

The next day, Vincent Van Gogh is taken to a hospital to recover and Paul Gauguin leaves Arles. They continue to correspond until Van Gogh’s death.

Gauguin fathered at least eight children with at least three women

Paul Gauguin became notorious in the art world for his debauchery and many affairs—particularly with young, underage women. It begs the question: Can you love the work and abhor its creator? Can—and should—you separate the art from the artist?

As a stockbroker, Gauguin met and married Mette-Sophie Gad. They had five children: Émile, Aline, Clovis, Jean-René, and Paul Rollon. After he lost his job, the family moved to Copenhagen. By this time, Gauguin aspired to paint full-time. Mette couldn’t understand his creative pursuits. The marriage disintegrated and Gauguin left his family and returned to Paris.

Gauguin had many young mistresses. Many of them from Tahiti were under the age of 15. Most notable of them was Teha’amana. In a single afternoon, she and Gauguin were introduced and then married. Teha’amana was 13. Eventually, she bore a son, Emile Marae a Tai.

Back in Paris, Gauguin had one more daughter, Germaine Huet, with his young mistress Juliette Huet.

Gauguin would outlive two of his children: his daughter Aline and his son Clovis. Three of Gauguin’s children became artists: Paul Rollon “Pola” Gauguin, Emile Gauguin (Emile Marae a Tai), and Germaine Huet (under the name Germaine Chardon).

Historians believe he might’ve had more children than we know of.

He was also completely enamored with the primitive life

In 1887, together with fellow artist and friend Charles Laval, Paul Gauguin sailed for Panama and Martinique. Unfortunately, their stay was cut short. The two artists contracted malaria and returned to Paris to recover. Nonetheless, this trip transformed Gauguin’s outlook.

Suffice to say, Gauguin hated modern life. He left Paris to settle in Brittany. But even that wasn’t exotic enough. Gauguin obsessively searched for meaning through a “pure human existence.” One that was free from western tradition and European mentality. In other words, Primitivism.

For someone who rejected capitalism and colonialism, Gauguin’s view is westernized and idealized.

Gauguin made his way to French Polynesia expecting the opposite of western urbanization. Instead of a lost and unmarred island paradise, he found a developing city under French colonization.

The island life was still largely inspiring. Gauguin produced his most spiritual and mystic works here. But his resources dwindled. Paul Gauguin would return to France once more to exhibit his work. Only 11 of his 44 paintings sold.

Gauguin painted his magnum opus shortly before attempting suicide

Gauguin returned to Tahiti after a failed exhibition. He took up residence in the Marquesas Islands—the last place he’d ever go. He arrived in Tahiti alone, in debt, and in poor health. Gauguin isn’t so much a creative hero. He was a man of many vices, and these all caught up with him in his later years.

To make matters worse, his favorite daughter Aline died in 1897. Gauguin began to question his own mortality. Stuck in a deep depression, he turned to art.

Gauguin got to work on his largest and arguably best work of all: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? In some ways, this painting is a final farewell. In a letter to his friend, Daniel de Monfried, Gauguin talked about suicide. Where Do We Come Frome would be a culmination of his life’s work.

After completing the painting, Gauguin attempted suicide by self-poisoning. He survived, recovered, and lived to paint for a few more years. He died of a morphine overdose and heart attack in 1903.

Paul Gauguin lived in relative poverty and his work received commercial success only after his death

The myth of the starving artist seems true when you look at Gauguin’s life. After losing his stockbroker job, he had to adopt a more modest lifestyle. More so when he settled in French Polynesia.

He was able to sell some paintings for low prices. Gauguin wasn’t well-received by art critics and art collectors when he was alive. His Synthetist style was considered too avant-garde.

Art historians consider Gauguin’s last years to be most enigmatic. Many of his letters, works, and belongings were auctioned in Atuona—if not destroyed for their “pornographic nature.” He is buried on Hiva Oa but denied a Christian burial as he upset many of the island missionaries.

Ironically, Paul Gauguin’s painting When Will You Marry became one of the most expensive artworks in history. In 2015, it was sold for $300 million to an unknown collector.

Also, there’s a crater on the planet Mercury named after Paul Gauguin. The craters on Mercury are named after famous artists, musicians, and writers.

Where can you find Paul Gauguin’s famous works?

Some notable characteristics of Paul Gauguin’s signature synthetist art style include: bold, expressive brush strokes and vibrant, flat areas of color with thick outlines. Paintings of this style synthesize an object's essence versus focusing on traditional form and perspective.

Here are some of Paul Gauguin’s best works you should know of—and where to find them.

Self-portrait with portrait of Bernard, ‘Les Misérables’ (1888) The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Gauguin often identified as a troubled, misunderstood, and persecuted soul. Here, he portrays himself as Jean Valjean—the main character in Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables.

This painting represents his time in Arles and his close friendships with Vincent Van Gogh and Émile Bernard. We see the latter in a portrait-within-a-portrait on the upper right. The trio of artists exchanged portraits with each other to commemorate their then harmonious relationship.

The Painter of Sunflowers (1888) The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

This is a portrait of another art legend at work. All through the eyes of an equally great artist. On seeing the portrait, Van Gogh remarked, "My face has lit up, after all, a lot since, but it was indeed me, extremely tired and charged with electricity as I was then."

Vision After the Sermon (1888) Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

During his time in Pont-Aven, Brittany, Paul Gauguin’s art transitions out of his early impressionist roots and matures into synthetism. Much of his paintings from this time show the simple lives of local Breton peasants. This painting is one of the first important works in the Synthetist art movement.

Departing from accurately capturing the impression of light and shadow, Gauguin starts to synthesize the subject with his emotions and imagination. Gauguin depicts what a group of peasant women see after a church sermon: Jacob wrestling with an angel. The perspective is purposefully skewed—the holy is separated from the worldly.

The Yellow Christ (1889) Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

At first, the color can be quite jarring. You may think, “What’s up with a yellow Jesus?” Well, this is an essential piece of Cloisonnism, a prime example of Gauguin’s (then) new and developing art style. It evokes the cloisonné technique in enamelware in which metal wires are shaped into outlines and filled with colored glass.

You wouldn’t picture Christ’s crucifixion in the autumnal fields of 19th century Breton, but Paul Gauguin did. We see Christ surrounded by Bretonian women. This figure of Christ is modeled after a crucifix in the Pont-Aven church. It’s more about Gauguin’s feelings and imagination, more than it is an accurate portrayal of a subject.

Jesus Christ is a recurring figure in Gauguin’s body of work. He often felt lonely and misunderstood, comparing his suffering to that of Christ himself. The Yellow Christ makes a later appearance in the background of another self-portrait.

Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake (1889) National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Gauguin found the growing artist colony in Pont-Aven too crowded. He relocated to an inn run by Marie Henry in a fishing village called Le Pouldou. There, he and a smaller group of artists painted every corner of the inn.

This self-portrait was on one of the cupboard doors. It shows Gauguin’s fascination with religious and spiritual symbolism. Gauguin makes this self-portrait like it’s a caricature. He only paints part of himself. We see his head, a vague form of a hand, and symbols that deal with dualities: good and evil, heaven and hell, temptation and sin.

The Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892) Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

Allegedly, Paul Gauguin came home late at night and frightened his young wife Teha’amana. We see here the teenage girl lying naked and afraid in bed while a hooded tupapau (Tahitian spirit of the dead) watches from the shadows. Teha’amana, whom Gauguin also called Tehura, was a frequent subject of his paintings.

Gauguin explores many philosophical dualities and universal truths. Light and darkness, youth and age, the “primitive” Tahiti and “civilized” Europe, the contrast between life and death.

You can interpret the painting in a lot of ways. Why did Teha’amana see a spirit in the place of Gauguin? Is Gauguin portraying himself as a figure of death and old age on purpose? What does this painting say about their marriage—now controversial in the eyes of art historians?

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Sick, impoverished, grieving, and depressed in Tahiti, Gauguin got to work on his manifesto. A magnum opus meant to be his largest, greatest, and last work.

Almost four meters wide and over a meter tall, it’s a visual essay that reflects on the cycle of life and death. Quite like an ancient scroll, the painting is meant to be “read” from right to left. You can divide or group the painting into three stages—each reflecting the three questions posited in the title. We see birth and the beginning of life, adulthood and the struggle of daily existence, and finally death and divinity.

The painting asks us to ponder the meaning of life and death and beyond. How would you read this piece?

What are your thoughts and feelings about Paul Gauguin?

We hope you learned a little (or a lot) more about art history through this piece. So what do you think about Gauguin as a person and as an artist? What do you think is the answer to the questions in his final work?

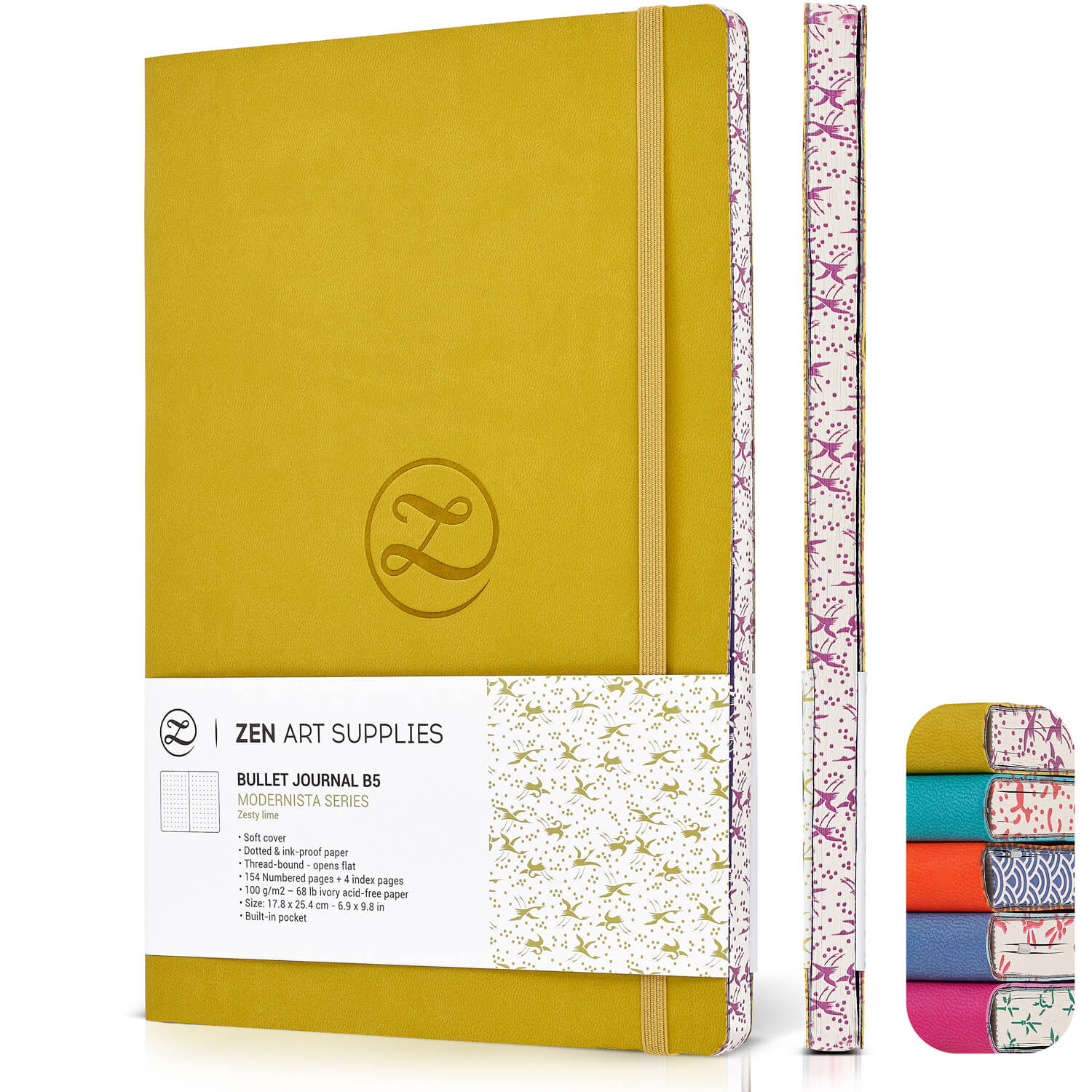

Every month, the ZenART blog features a famous person in art history. People like Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Édouard Manet, and Claude Monet! Got a fave artist we haven’t talked about yet? Someone you’d like to learn more about? Drop their names in the comments section below! And stay tuned to our Inspiration section for our next icon of art history.